Street Art & Shophouses; How a Colombo Community Fights to Save their Heritage

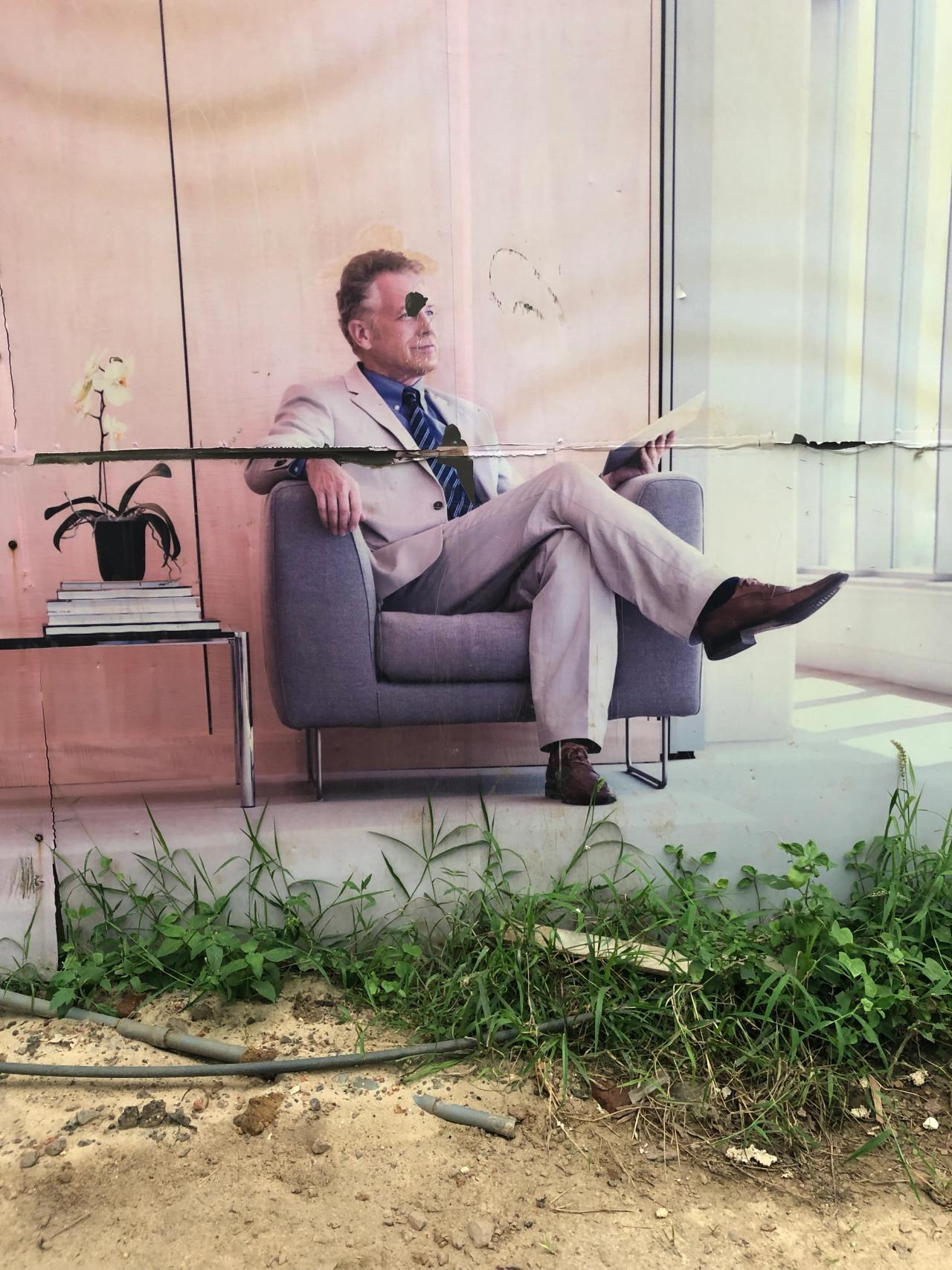

Colombo, Sri Lanka’s capital is undergoing a make-over. After years of civil war the city is set to become a Singapore-like economic powerhouse. Chinese and Indian fuelled investment has poured in to make this dream come true. But at what cost? Slave Island is an old neighbourhood in the heart of the city where skyscrapers are going up faster than one can imagine. What used to be a unique and vibrant urban district is being transformed beyond recognition, swallowed up by the shiny new apartment buildings rising around it. Artist Firi Rahman has lived his whole life in Slave Island. As he saw the destruction happening before his eyes, he started a campaign to save the soul of the neighbourhood. "#WeAreFromHere” is a unique artistic initiative that maps stories of ordinary and extraordinary locals to highlight the unique multicultural community of Slave Island. Now, as an iconic row of historic shophouses, considered by many as the face of Slave Island is threatened by demolition, we join Firi and his friends and take a look at why this place matters so much to the local community.

Giving the invisible community a face

Slave Island - locally known as Kompannaveediya - has lived so many lives. In the colonial days - when it still was an island in a crocodile-infested lake - the Portuguese and later the Dutch considered it the ideal location for a slave prison. The name stayed long after the slaves were set free. Later it became a military station until the British transformed it into the country’s first botanical gardens. It was 1810, not very long after they had taken Colombo, and the area became a popular pick-nick spot. Being so centrally located the garden was slowly swallowed by the urban jungle around it and the area grew into what it is today, a hub of vibrant activity where African, Indian, Javanese, Burgher, Moor and most prominently Malay heritage are visible at every street corner. Heritage of those who once came here as slaves. You can hear it in the music, see it in the colours and taste it in the food. No longer an island, it is a diverse community that is unique in Colombo. People of all faiths live together in colourful small alleyways, be it Christian, Muslim, Hindu, or Buddhist.

Location, location, location

Slave Island is about to undergo another reincarnation. The location just south of the city’s Central Business District Fort is triple A, so the small alleyways became valuable property. The eviction of residents in an area of approximately 160 acres in the heart of Colombo 02 began in 2012. Seventy thousand households are being relocated to newly constructed apartment-style housing in other parts of the city. It is part of an ambitious USD287 million ‘City of Colombo Urban Regeneration Project’ spearheaded by the Urban Development Authority fuelled by Chinese and Indian money. The scale and speed of the project is mindboggling with some streets simply being erased from the map and with it the social fabric and memories of place. Java Lane, a little laneway is one of them. The only thing the developers left standing was the green-white neighbourhood mosque, now surrounded by nothing but apartment blocks, disconnected from its community.

“Slave Island is undergoing a huge change now. Tall, shiny buildings are taking over the old, colonial architecture. We no longer have the old people here. They’ve all gone away. It’s sad, and because of that, we’re losing our sense of community” says Amir Inthizam, owner of a picture frame shop on Sir Henry De Mel Mawatha Street, one of the oldest businesses in the neighbourhood. He has lived through the better (or worse) part of Sri Lanka’s multi-coloured history.

Slave Island is undergoing a huge change now. We’re losing our sense of community.

Telling the story of the neighbourhood

The effect of the mural project was that Slave Island’s many little laneways were uplifted and connected with an invisible artistic thread.

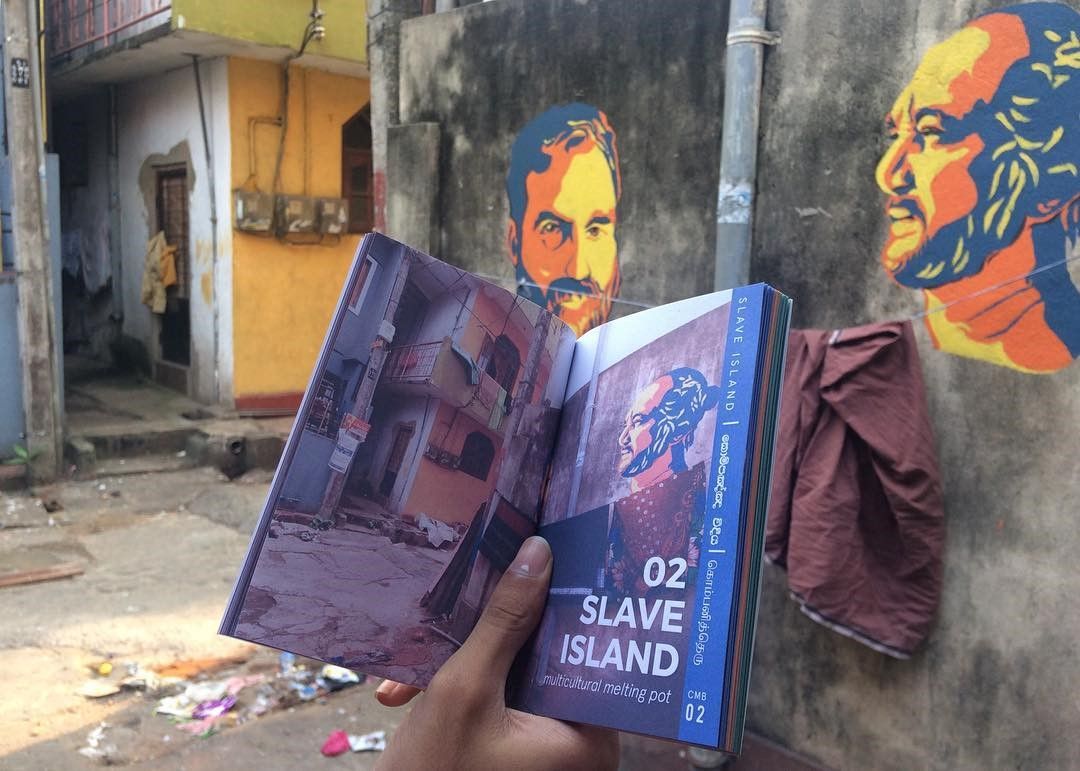

Slave Island-based artists Firi Rahman and Vicky Shahjahan's started “Wearefromhere” in 2012. A visual project portraying the people that make up the unique neighbourhood that Slave Island is. Their wall murals feature people from the community: sportspeople, street vendors, mechanics, musicians, actors and artists. Firi shares: “Slave Island is often perceived as an area filled with criminals, drug dealers and danger. It is also a place that is fast changing and disappearing, being swallowed up by the rapidly “modernising” Colombo. #WeAreFromHere showcases the people who make Slave Island a fascinating, unique and diverse place”.

Firi and his friends wanted to document places that maybe disappearing from the streetscape. “There are many places that have been demolished or damaged already, like the popular Castle Hotel and the Java Lane mosque. There are many more places, where we don’t know whether they’ll still be here in a few years’ time, like the famous Rio Cinema, or the iconic row of De Soysa shop houses. That street already changed beyond recognition with the big skyscrapers, you can no longer see the sunset because of these new tall buildings.” Says Firi. But more than just the buildings, the project wanted to document the local community. They collected stories from ordinary and extraordinary residents and turned them into wall murals. Firi adds: “It’s a time of rapid change for us and we’re all adjusting. I want to give people the feeling that this place, its heritage and culture have value. With all these new buildings they may feel that their land and their properties can be bought just like that. I tell the stories of the community, to make people feel proud of their place.”

Value of place for the community

Firi started by recording voice cuts of the conversations and he was soon joined in his artistic journey by local artists Parilojithan Ramanathan and Vicky Shahjahan. Wanting to make it more interactive, the trio decided to draw portrait murals of the people around Slave Island. “We first wanted to make one big mural, but they decided to spread them through the neighbourhood to better blend in with the urban fabric, not create disruption and get more traction,” says Vicky.

One of the persons we ‘meet on the walls is Fazil, a respected member of the local society. His portrait tells the story of how here in Slave Island, funerals are the occasion of togetherness for people, irrespective of their faith. We then meet ‘the captain’ a popular car repair man, Rifakath a known rugby player and Milan a street cart vendor, each with their own story that we learn through a set of accompanying cards. We later meet Milan in real life and buy a faluda from his cart. “It’s like a treasure hunt, but with people! You get a card of a person, and you have to find the respective wall mural. The idea is not just to get to know a person, but also find out how they matter to the community.”

The mural project proved a trigger point, an outlet for many concerned citizens and an opportunity for them to communicate the value of the place to others. What followed was a series of #WeAreFromHere walks, talks, exhibitions, gatherings and celebrations. The effect of the project was that Slave Island’s many little laneways were uplifted and connected with an invisible artistic thread. What started as an art project became the face of the resistance against the big developers, the voice of the community.

Saving de Soysa shophouses

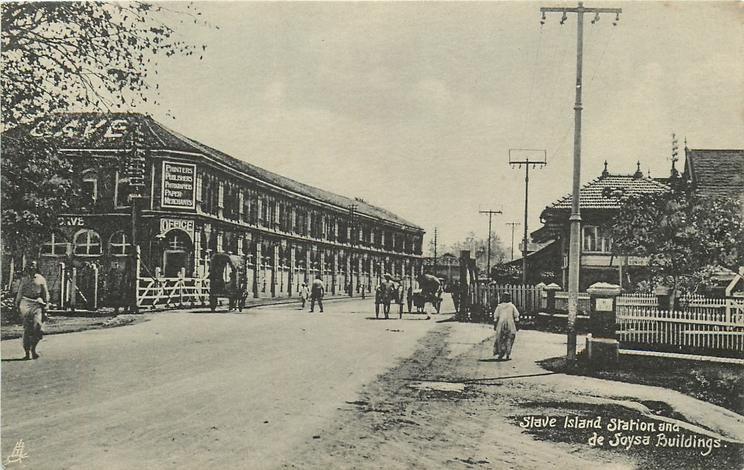

Now a new challenge has surfaced for Firi and his friends. De Soysa Buildings, a pastel-coloured row of shop houses opposite the Kompannaveediya train station holds the honour of being the longest intact colonial shop house road frontage in the country, but it may not be there for much longer. The iconic street will suffer a similar fate to that of the nearby 140-year-old Castle Hotel which was demolished in May 2017. Yet, many locals feel the shophouses are key to Slave Island’s unique heritage, being built in 1870 by famed philanthropist Charles Henry De Soysa, the wealthiest Ceylonese of the 19th century and brains behind the first bank in the country.

It was a landmark building in those days and one of the earliest examples of shophouse design in the city. A prestigious address, here was the headquarters of the esteemed Cave&Co, the country’s leading publisher. “The story goes that in the 1920s and 30s the premises of H.W. Cave & Company was considered one of the most fashionable addresses in Colombo” says local architect Ismeth Raheem.

The glamour of those days may be gone. Once a prominent street, now you find dry cleaners, tailor shops and cheap café. The shop houses are a bit run down with creaky staircases and paint peeling off the pastel-coloured facades, but the signature architectural style remains unique and synonymous with the face of Slave Island. Fifty-year-old Kareema Anwar Deen has lived in the Soysa building for 18 years, above Ceylon Cleaners which has occupied the space since 1934, she points at the solid wooden floors and says: “These are strong enough to run on.” Ranil de Soysa, a great-grandchild of the original owner agrees: “There is history in every block and beam of the Soysa building: from the people who have worked and lived here for decades to its distinctive colours. Some things once lost cannot be replicated.”

Firi, Vicky and many others in the community are lobbying to get the row of Soysabuildings listed. Academics, architects and international experts have come to the scene and unanimously pointed out the solid structural condition of the properties and their unique heritage value. But yet to no avail. In September 2019 Nihal Rupasinghe, Secretary to the Ministry of Megapolis and Western Development said “There was also no legal obstacle to demolition, the Archaeological Department has not officially recognised the Soysa building as being of heritage value and thereby requiring protection” when asked about the fate of the iconic row of shop houses. “The Urban Development Authority (UDA) will grant the developer, Tata Housing, permission to carry out the demolition.”

If Colombo wants to be like Singapore, why don’t the city leaders preserve the shophouses and use it as an asset to create a unique world-class urban district with a distinct identity?

Singapore style heritage preservation?

One cannot help but wonder if Colombo wants to be like Singapore, why don’t the city leaders listen to the voice of the Slave Island community? Elsewhere in Asia, with Singapore as a leading examshophousesouses are protected by strict regulations and are premium spaces for apartments and shops. The Lion City’s planners have successfully used mundane dilapidated properties as strategic assets for creating world-class urban districts with distinct identities. ‘Conservation shop houses’ are now a much-copied component of the Singapore signature style. Slave Island without the Soysa shophouses is like a neighbourhood without a soul.

It’s a tragic loss for the country. A loss not only for me, but for the whole country.

Update

This article was first published in 2019, shortly after the UDA (Urban Development Authority) earmarked the properties for eviction and demolition. Ever since the community persuaded the Department of Archaeology to list the building under the Antiquities Act. In 2020 they also campaigned to get de Soysa shophouses on the World Monuments Watch List. All was in vain. In June 2021 a section of the De Soysa building (facing Malay Street) collapsed. Years of neglect had taken their toll, it was too late. This was the final episode of the Soysa story. A piece of history has been bulldozed to make way for an anonymous urban future.

#WeAreFromHere

The WeAreFromHere community continues to collect souvenirs, picture albums, and sound recordings to build an audio-visual community archive that narrates stories of individual families and captures the collective memories and unique sense of community. Find them on facebook or instagram and when you're in Colombo, reach out or explore the Slave Island neighbourhood with this self-guided storywalk.

Credits

Created by

Powered by

Designed by

Written by

About

Colombo Heritage Collective

Colombo Heritage Collective is an NGO that cares for Colombo’s heritage and looks for ways to preserve the city’s unique identity in a time of rapid urbanisation.

www.facebook.com/colomboheritagecollectiveDutch Culture

The Shared Cultural Heritage Fund of Dutch Culture supports projects that contribute to the visibility of the shared history that connects the Netherlands with Sri Lanka.

internationalheritage.dutchculture.nl/enFiri Rahman

Firi Rahman is an artist who lives and works in Slave Island. He captures the uniqueness of place in his conceptual cartography and ink pen drawings. Firi loves to wander, photograph abandoned places, and learn the stories of forgotten corners. Among his many passions is Firi’s love of parrots: “I live in my own urban jungle”.

@ifiriNadeesha Paulis

A weaver of words and a lover of getting lost in a jungle or in her own mind, Nadeesha believes that genuine connections within us, being one with nature and dance can heal everyone.

@nadeepaws