Beyond Galle Fort's Facades: Sketching the Layers of Its Architectural Legacy

On Sri Lanka’s southern coast stands a living testament of a complex colonial past. In Galle Fort, Singhalese settlers, Muslim and Chinese traders, and Portuguese, Dutch and British colonists left their distinctive marks. The legacy of this fortified peninsula is more than an intriguing hodgepodge of structures; it is a unique multicultural blend of architectural ingenuity that merges European and Asian influences. Every house in the Fort tells a story that echoes a distant past, and together, the properties create a streetscape with a distinctive rhythm of exceptional beauty. In 1988, the Old Fortified Town of Galle was designated as a UNESCO Living Heritage Site in recognition of its history, architecture and the life that unfolds every day.

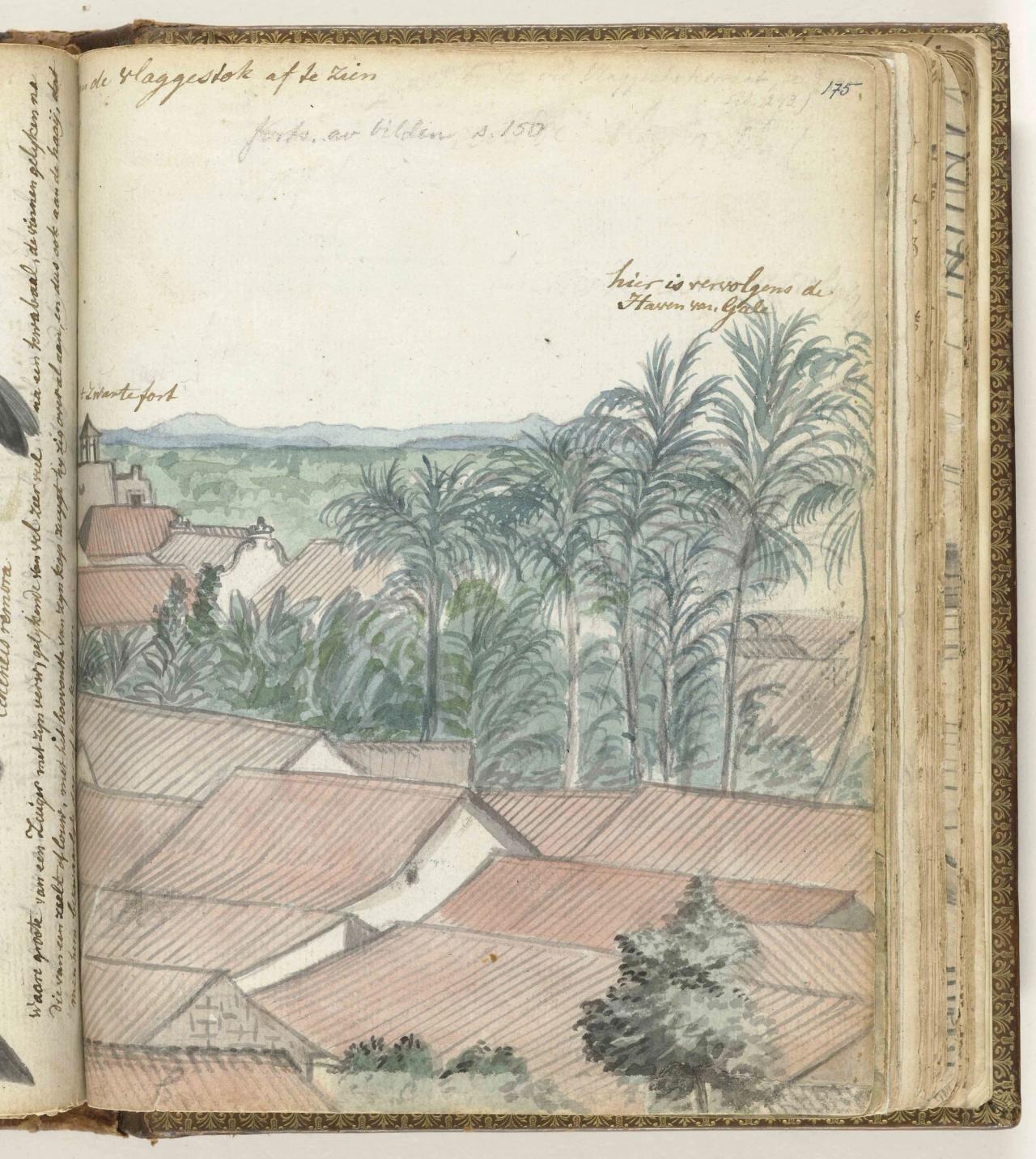

When you wander within its walls, you will imagine yourself in the 17th century. The town’s unique character invites visitors from all walks of life to stroll the cobbled street and take lots of photos. But what if it is also possible to look beyond the eclectic, elegant facades to find out more about the different architectural and historical layers?

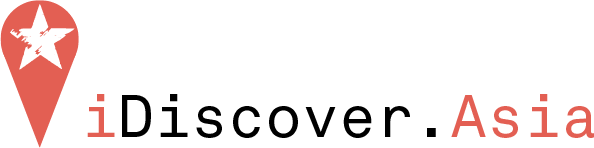

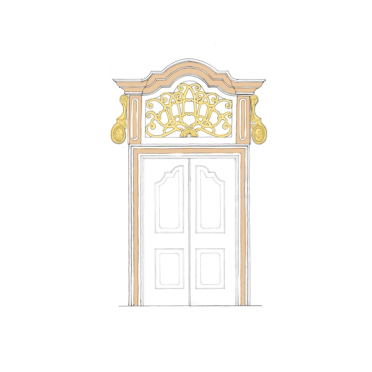

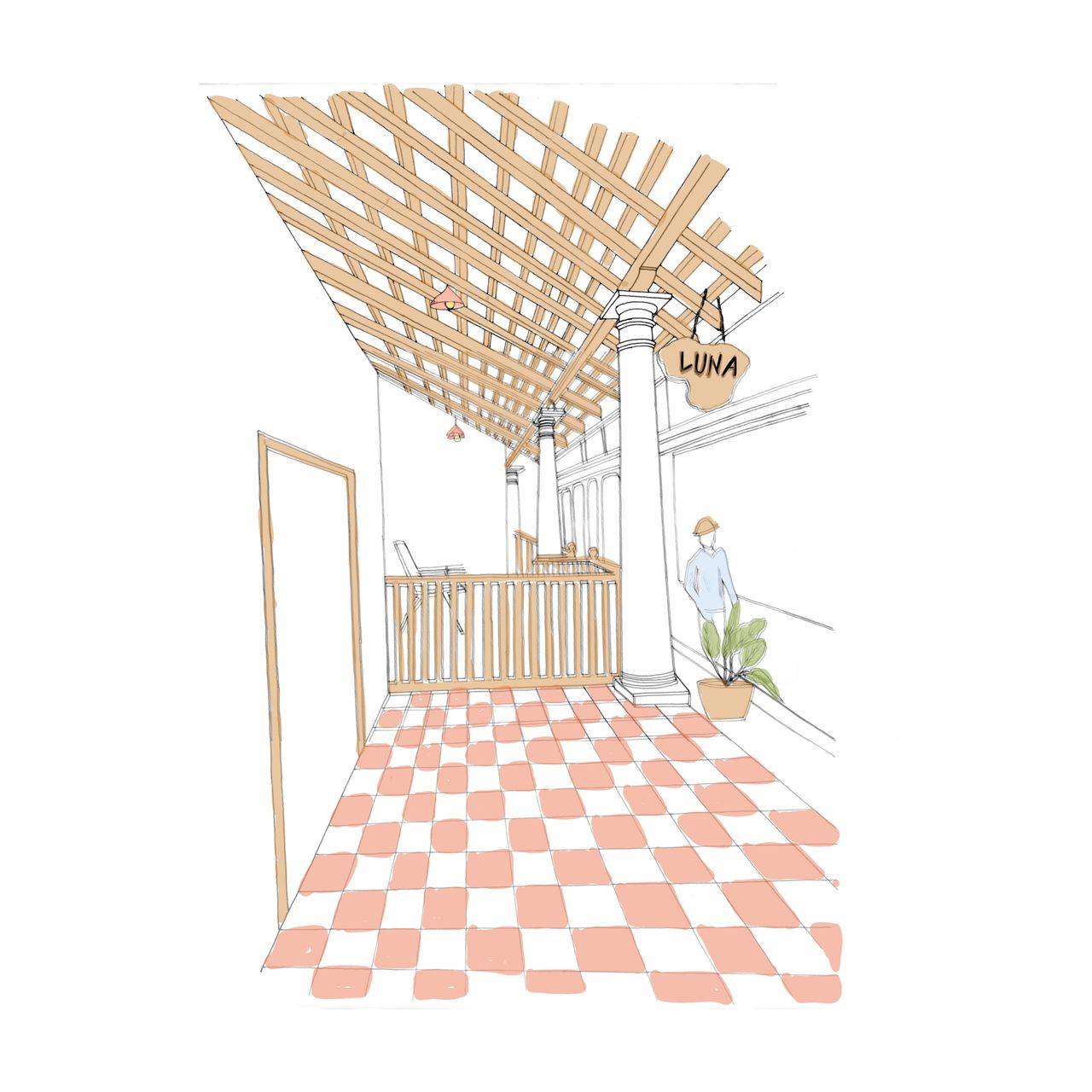

Students of the Department of Architecture at the University of Moratuwa took to the streets to explore Galle’s built heritage. They selected 12 archetypical properties and spent time talking, observing, analysing, and drawing the different architectural influences and intricate details, from the verandas to the large living quarters, small back rooms, and charming inner courtyards. The students produced beautiful hand-drawn sketches — in pencil and ink — of Galle Fort's historic dwellings, plans, sections, elevations, and perspectives to decode its architectural beauty and peel back its different architectural and historic layers.

What really draws me to Galle Fort is its fusion, a wonderful mix of architecture and culture.

A Multicultural Melange

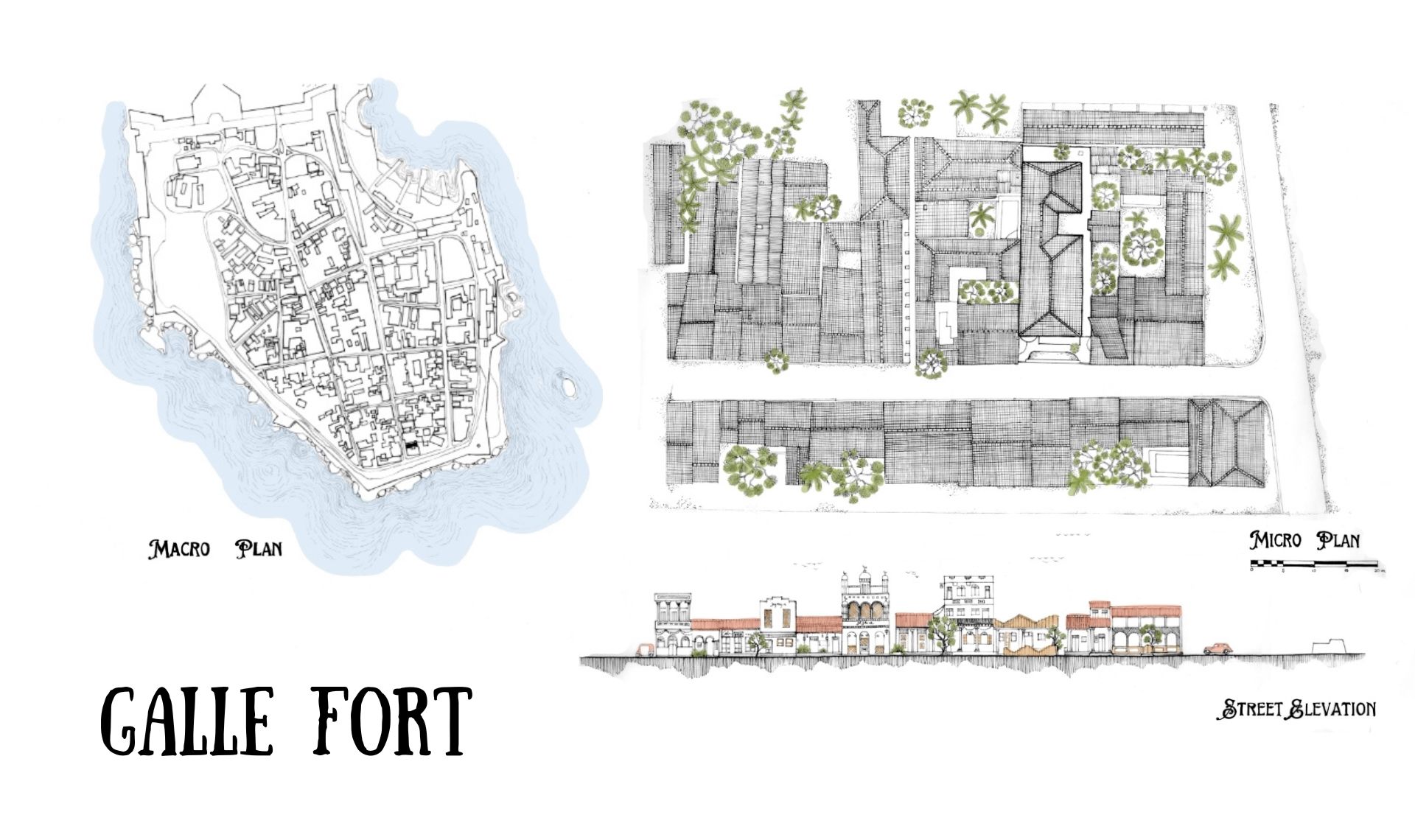

An old myth tells of Sinbad the Sailor’s legendary voyage, where he peddled on his raft into blue waters and stumbled upon a river full of gems in Ceylon, the city of the king of Serendi. Sinbad’s story — fictional or not — captured the imagination of many. The island of ‘Taprobane’ is prominently featured on Ptolemy's World Map from the 2nd century as a trading point connecting Greece, Arabia, and China. Many explorers followed in Sinbad’s footsteps, including the Venetian Marco Polo, Moroccan Ibn Battuta and Chinese General Zheng He, who came to the shores of Ceylon to trade in spice and gems. In the 16th century, the Europeans arrived, who then had to wrestle the Arab and Chinese traders to gain control of the coast. Their fortifications marked the beginning of over 400 years of colonial domination and made Galle the epicentre of Asian-European trading.

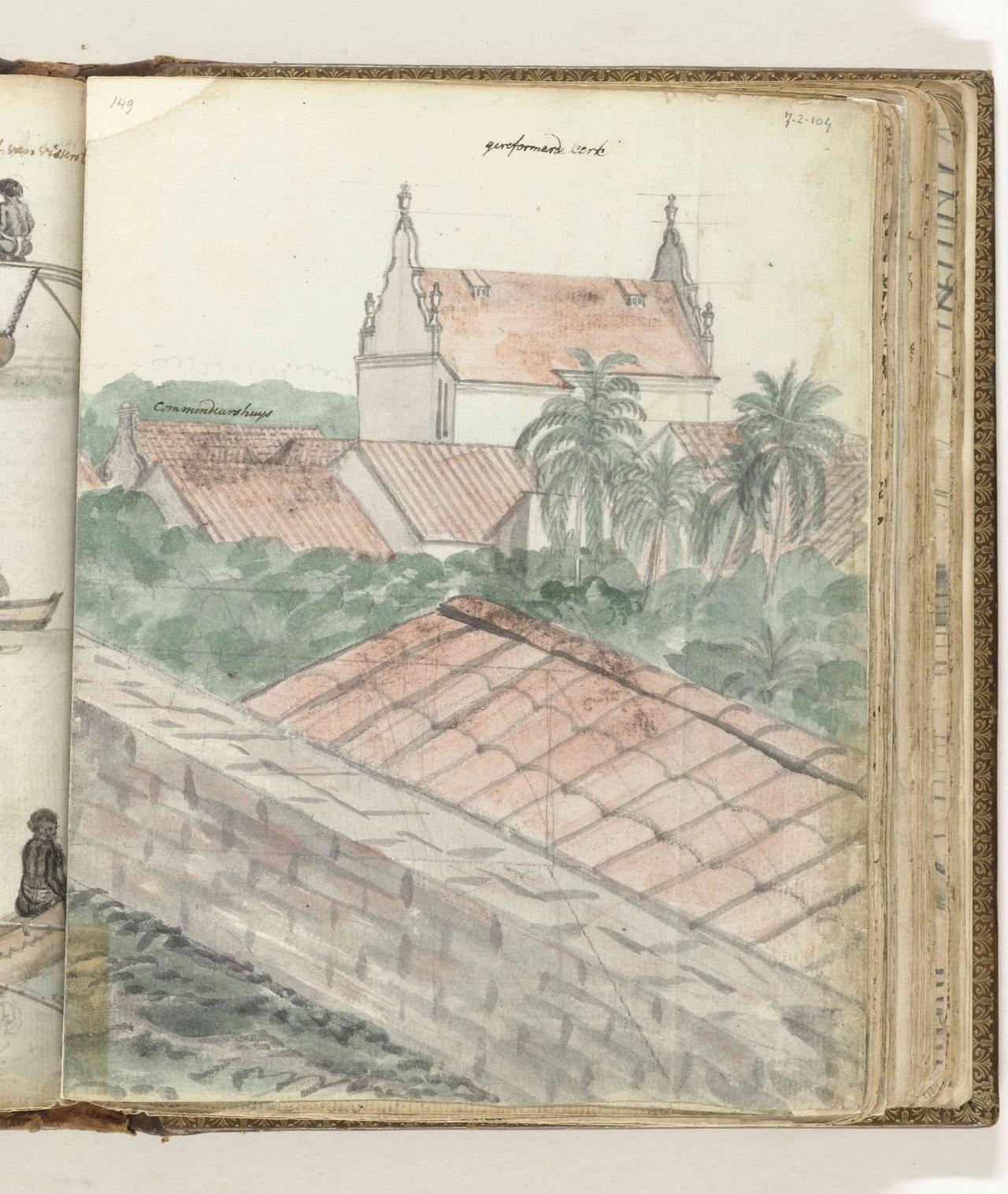

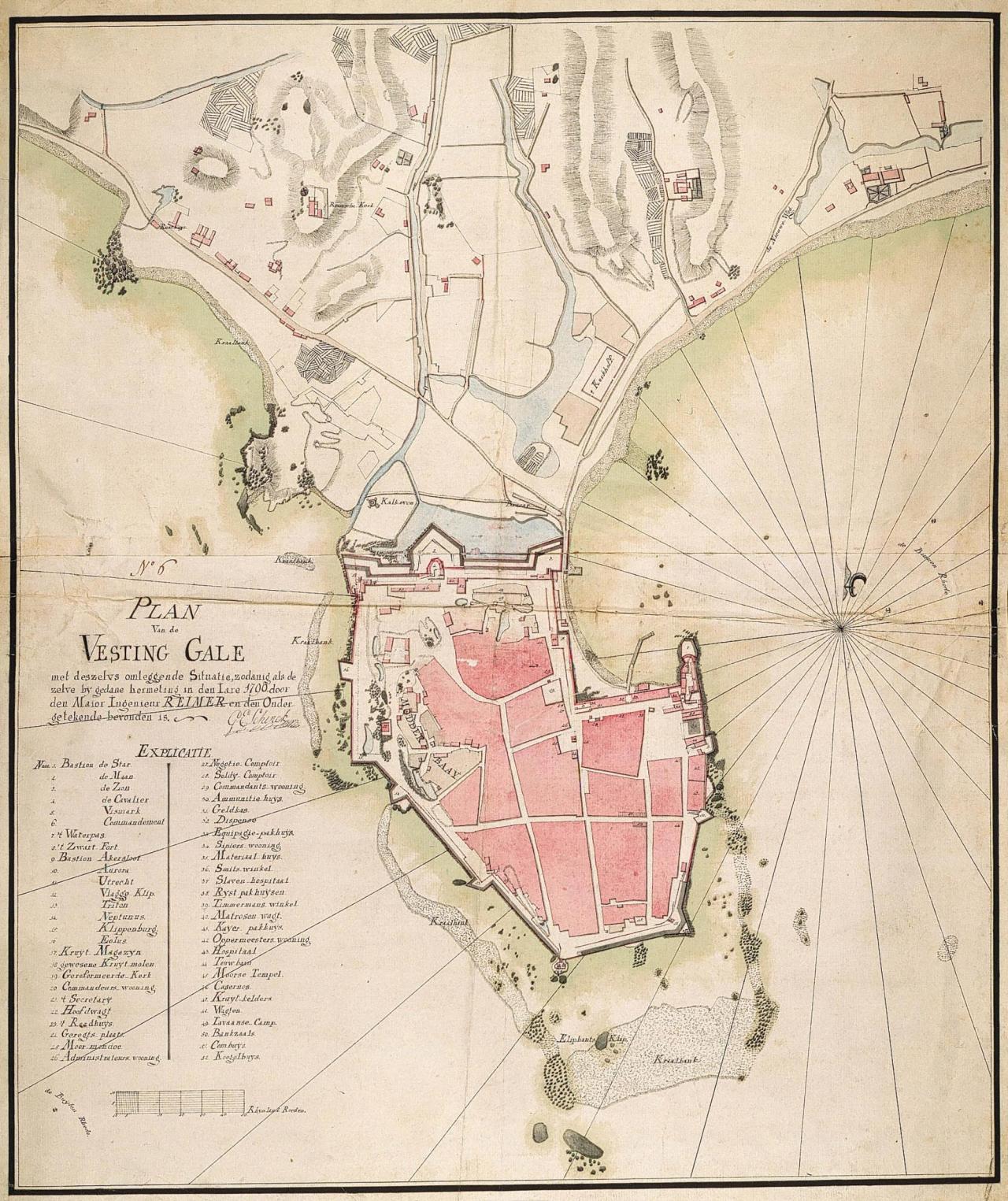

The Portuguese first built a Franciscan Chapel in 1543, and a few decades later, they constructed Santa Cruz de Gale, a fort for defence purposes. In 1640, a fleet of 12 Dutch ships carrying 2000 soldiers launched an attack on the Portuguese Fort. After a brief battle, the Dutch gained control of the Fort. In the Dutch Period, Galle became the most important harbour on the island. The Fort was expanded, and the colonial township developed into an international trading hub. In 1796, the Dutch surrendered the Fort to the British, who subsequently occupied it from the late 18th century until Sri Lanka’s independence on February 4, 1948. Yet, the British were more focused on Colombo and made fewer interventions in the already well-developed township of Galle Fort.

Fort’s uniqueness is a result of the many different influences continuously at play across five centuries. The colonial powers occupying the Fort may have changed over time, but there was a constant presence of trading communities, both indigenous — Sinhalese and Tamil — and from Arabia, India and the Far East, all living together within the protection of the massive city rampart. Galle Fort’s architecture reflects this shared past and a testimony to the town’s diversity: it houses a wide range of architectural styles including Dutch-Ceylon hybrid architecture, British architecture, Art Deco, and post-colonial architecture, which coexist in a harmonious spatial composition.

The Dutch-Ceylon hybrid is one of Fort’s significant architectural styles, sprung from adaptations of traditional Dutch architecture that respond to the local climate and social fabric, think of elements like verandas, internal courtyards, and screens.

Fort has so much significance as a living colonial heritage site. We are trying to restore the original streetscape and preserve the buildings. We have to protect it for the next generation.

Dotting the Streets ‘Dutch Style’

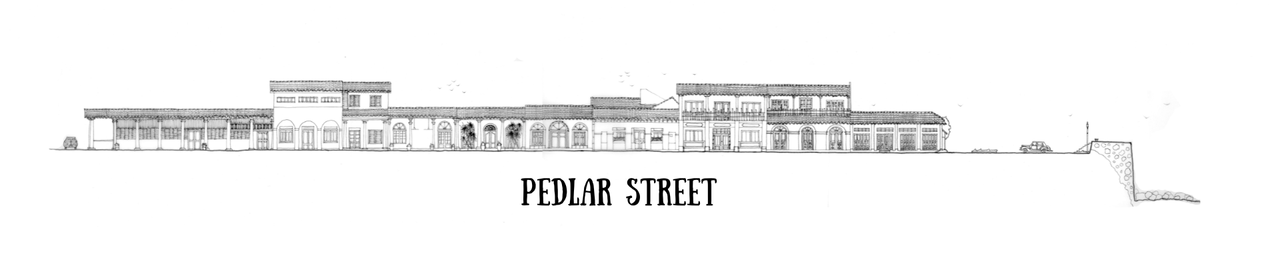

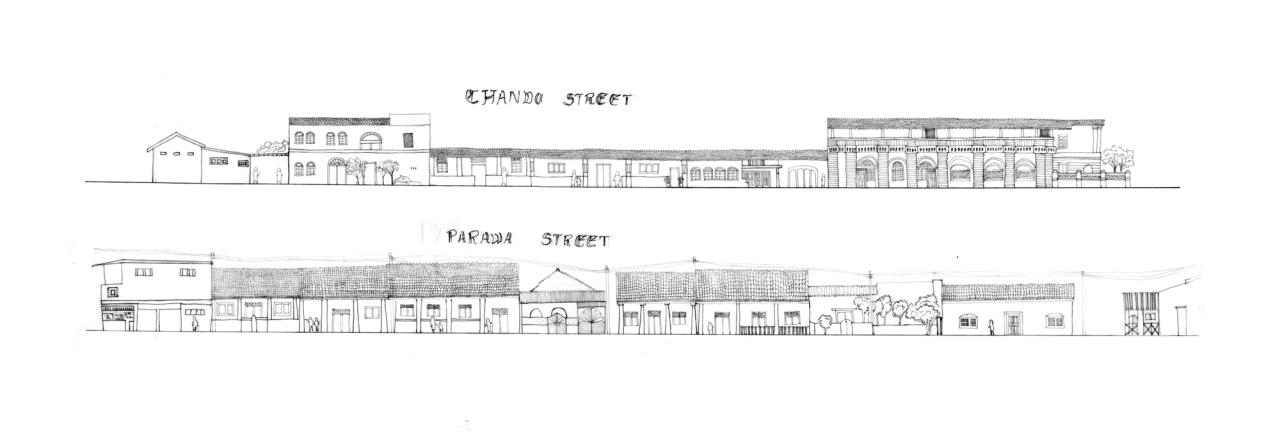

In the Dutch period — the 17th and 18th centuries — Galle Fort was home to warehouses, stables, mansions, cottages, religious buildings, a prison, a lighthouse and a hospital, all neatly dotted across the well-designed, efficient town plan with a grid pattern, protected by 14 bastions and hundred and nine cannons. About 275 families, among whom several ethnic groups and local families, lived within the fortress city. In those days, Leyn Baan Street (Lijnbaanstraat) was the main street. The architecture introduced by the Dutch — a combination of western design and local technique — is still predominant in the streetscape of the Fort.

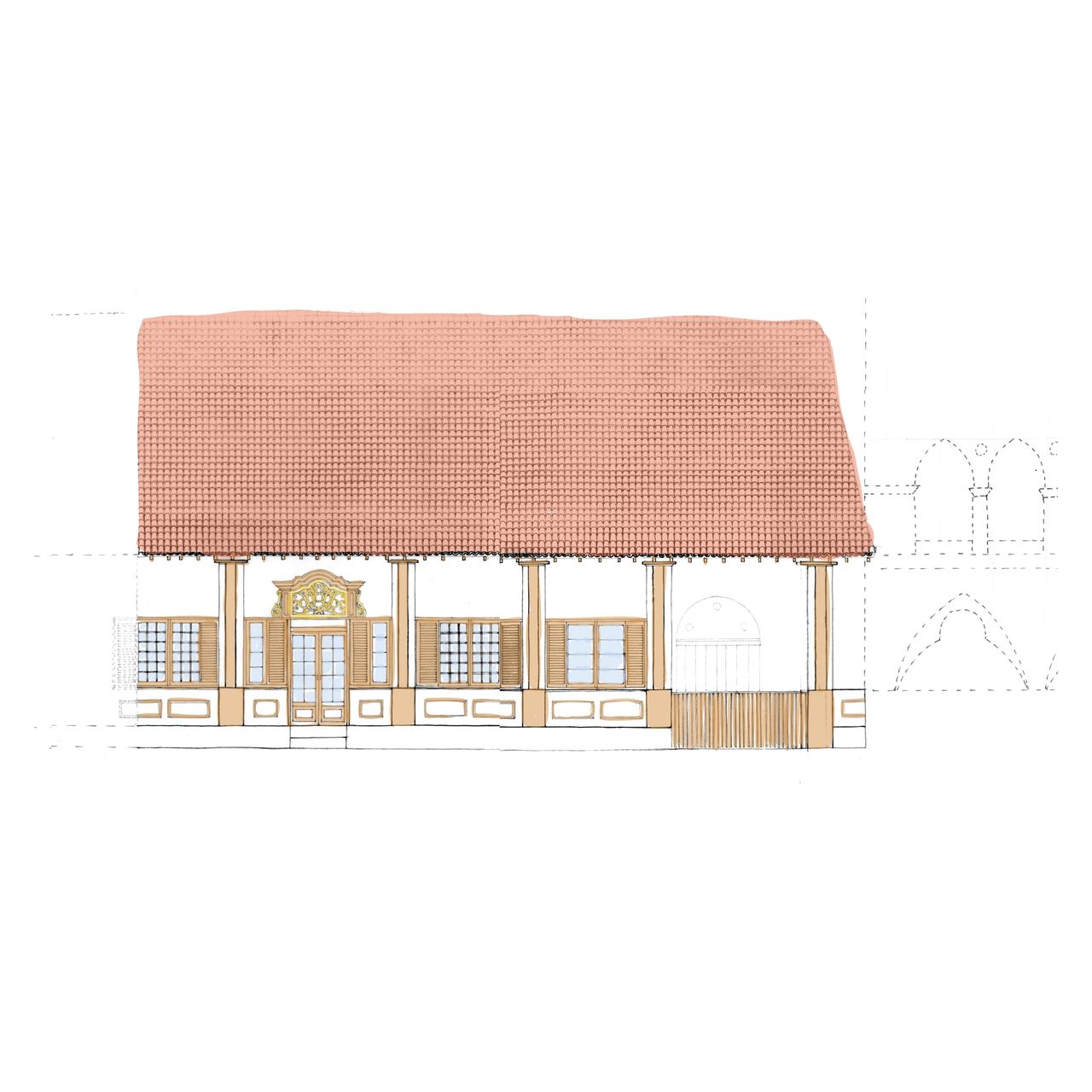

The white-plastered Dutch houses, homes of traders, governors, merchants and missionaries, were located directly at the street, boasting solid coral walls and overhanging roofs made of terracotta-coloured clay tiles. The open veranda, created by the sloping roofs supported by arched wooden or masonry columns, is the most important characteristic of the homes in Fort. Another feature of the Dutch typology are the large framed doors and windows and fanlights, small half-moon windows, to allow the wind to blow through the house and cool the rooms.

Typically, Dutch-era houses were single-storied on the street side, with an additional floor in the back. Behind the veranda and through the large wooden access door was the 'kleine zaal', small hall, flanked by one or two additional rooms. The great hall, or 'groote zaal’, followed this reception hall. This massive space, characterised by its high ceilings, would typically run through the width of the house and open to a rear veranda and open courtyard to provide optimum air circulation. This rear veranda, an intermediate space between inside and outside, was used as one of the main living rooms. The open courtyard, or patio, usually generously decked with greenery, was added to bring light and air into the deep properties and featured a pond, servant’s quarters or even stables.

Fusion Architecture Of Cosmopolitan Elan

Owing to popular architectural trends that have blown through the streets of Fort over the past decades, many of the buildings are renovated or altered to the imagination of what a Dutch building’ might — or even should — look like. Doing so erases not only the historical evolution of those buildings, but also distorts the Genius Loci, Fort’s communal identity and history. What many people forget is that the austerity of early Dutch and Portuguese architecture was followed by the eclecticism of Baroque and high Victorian frivolity. The British rarely demolished Dutch buildings; they preferred to embellish by adding design elements and merging or expanding living quarters. In those days, new properties were also built in Art Deco-style and even ‘modern tropical style’. These voguish structures were usually built outside the confines of the Dutch grid pattern. At Rampart Street, for instance, there are more examples of exotic period architecture creating a cosmopolitan streetscape cocktail.

Galle Fort is special because it’s one of the very few living fortresses in the world. It has a history of over 400 years and is an epitome of all communities living in harmony.

Drawing on the Past and Dreaming about the Future

More than just an architectural documentation project, the research and sketches of the students are created as a tribute to the residents of Galle Fort and appreciation of this wonder of architecture and urban design. It is a testimony of its living heritage, with different generations and cultures repurposing the buildings and adding their personal signatures to their homes. The students hope that going forward, the Fort will not give over to the monoculture of tourism, but will be able to maintain its residential character and keep its population as diverse as its unique streetscape.

About the Authors

Architect Rajitha Katugaha is a lecturer at the Faculty of Architecture, University of Moratuwa, Sri Lanka. He is an expert in history of art & architecture and was the year coordinator for this B.Arch Design Studio. Rajitha also serves as the secretary of ICOMOS Sri Lanka’s National Scientific Committee on vernacular architecture.

Dr. Ester van Steekelenburg is the co-founder of Urban Discovery, a non-profit that works at the intersection of cities, community and culture. On a mission to unlock the value of cultural heritage for the urban future, they partner with governments, developers and NGOs to build the business case for heritage revitalisation and work with schools and universities in heritage education and (re)interpretation projects.